Swansea’s 1930s Guildhall tower with trireme motives.

Fat ship prows jut out from the top of the otherwise gaunt sides of the Guildhall tower in Swansea. Facing the four winds they take the distinctive form of an ancient ship from the Mediterranean world, a jutting ram overtopped by a contemptuous scroll. I read that these were warships: biremes, triremes, quadriremes, quinquiremes and beyond, depending on the rows of slave oarsmen on each side. But I, as perhaps the architects of the 1930s Guildhall may have done, took my cue from John Masefield’s once popular poem and associated them with ancient trade.

Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir,

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine,

With a cargo of ivory,

And apes and peacocks,

Sandalwood, cedarwood, and sweet white wine.

‘Cargoes’, John Masefield (1902).

Bas relief from a Roman port near Naples.

In my 60s youth the most visible remains of Swansea’s great maritime trade were the misnamed banana boats that concealed stowaway tarantulas in their holds, in fact they probably plied the important Mediterranean trade routes. The ships were probably more akin to the last of the three contrasting verses of Cargoes – imaginary spiders apart, I was more gnawingly anxious about Monday morning when there would be the possibility that I would be the one to recite the poem by heart in front of the school class:

Dirty British coaster with a salt-caked smoke stack,

Butting through the Channel in the mad March days,

With a cargo of Tyne coal,

Road-rails, pig-lead,

Firewood, iron-ware, and cheap tin trays.

When you look out to the bay today, long bulk carriers lie low in the water, prows pointing towards the deep-water harbour at the immense integrated steelworks at Port Talbot. These ocean travellers were frustratingly anonymous until the internet lifted their anonymity. Coal from Australia waits at anchor in the Bristol Channel. Iron ore from Brazilian open-cast mines comes via ports such as Ponta Ubu. That the vast majority of the ore is shipped from that port to China is no surprise in light of recent developments.

Margam Xanadu

Further again around Swansea Bay, where the Glamorgan uplands turn inland and fields begin to cover a rich plain, the estate of the dynasty that put their name to Port Talbot sits rather incongruously. If the docks and steelworks were, and hopefully remain, the site of wealth creation for all, it is the nearby Margam estate that was a focus for conspicuous consumption. The Mansels bought the Margam Abbey at the Dissolution of the Monasteries – land, ecclesiastical and lay buildings. After four centuries of money making their descendants by marriage, the Talbots, brought the site to its final peak of development by raising a dominating 19th century Gothic mansion in what may be described as an ‘industrial baronial’ style, often most appealing when seen from a distance.

Over the centuries the estate acquired prestige collections. A deer park was an early example. As a 17th century agriculturalist dryly observed ‘[deer parks] make or preserve a grandeur, and cause them to be respected by their poorer neighbours’. At the end of the estate’s pomp in 1941, a four-day auction of the house’s contents including collections of furniture, silver, porcelain, books, tapestries and paintings that included works attributed at the time to Rembrandt, Canaletto, Gentileschi.

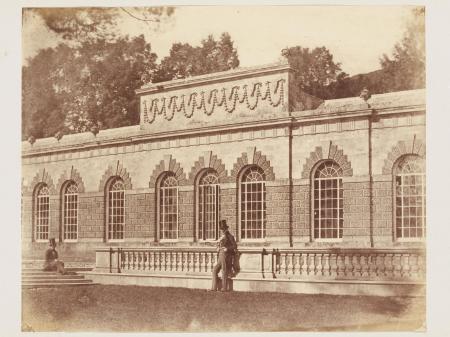

One of the estate’s early features was the ‘great’ collection of citrus trees whose scale and size were thought unequalled in Britain. The physical legacy of this collection today is the imposing Orangery at Margam. At 100 metres (327 ft) has been claimed to be the longest building of its type in Britain, perhaps Europe. Comparisons are difficult as people do not seem to measure these things in an ordered way. Nonetheless, the Margam Orangery has the air of one that believes it is the longest; in scale and character it is the Hallelujah Chorus of orangeries.

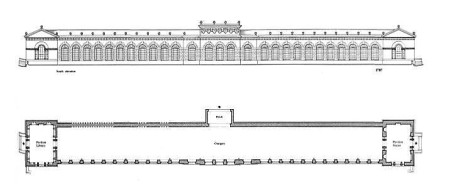

The ‘Hallelujah Chorus’ of orangeries, Margam.

A ‘citrus palace’, plan of the Orangery. (West Glamorgan Archive Service.)

East Pavilion, Margam Orangery. Where the TMT’s antique marbles acquired in Rome were displayed.

It was built in the late 18th century as a seasonal housing for an existing collection of citrus trees. It was a time when the function of Margam was as a pleasure park, which to this day gives the place the feel of a superior architectural backlot. The citrus trees have been a feature at Margam from the late 17th or early 18th centuries. The earliest documentation is from a 1711 garden book that records the task of putting the orange trees out of doors. We do not know where the trees originated, or at which exact period, but the trees inevitably came by sea originally. Legends inundate the breech where there is no written evidence. Some stories tell of them being taken as booty from Spanish ships, others of local shipwrecks. It is true that the coast here regularly acquired shipwrecks blown off-course when entering the south-westerly approaches to Britain. (See the ‘The Cultivation of the Genus Citrus.’ Paxton’s Magazine of Botany, and Register of Flowering Plants, Vol 1, 1841. [Quoting a manuscript found among Peter Collinson’s papers the author is still unresolved, cf. Lewis Weston Dillwyn, Hortis Collinsonianus, iv, note, 1843.])

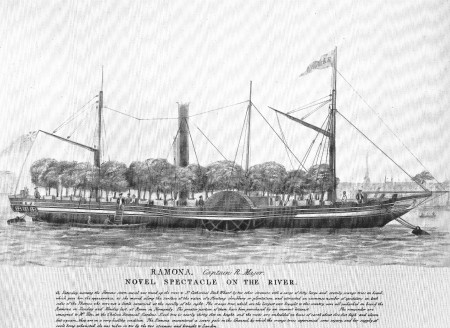

An early-19th century cargo of orange trees on deck of a steam ship at anchor the Thames. Shipped from Rouen to be shared by an ’eminent botanist’ and Chelsea Botanical Garden, Sloane Street.

The roll call of the benefactors and recipients of the allegedly beached citrus trees include: the King of Spain and the King of Denmark, Sir Henry Wotton and King James I, the King of Portugal and Catherine of Braganza, a Dutch merchant and Queen Mary II. Without a doubt a collection of citrus trees – a living embodiment of the warm south – was a worthy gift of sovereigns. Not as rare as a collection of Ming vases, possibly not quite as costly to keep as a stable of Arabian stallions but nevertheless an ostentatious show of wealth.

Phillip Miller’s revered The Gardener’s Dictionary (1754) details the care of new oranges trees ‘that are brought over every year in Year in Chests from Italy; which is, indeed, by much the quicker Way of furnishing a Greenhouse’.

Orange trees on the move at Versailles. (Detail from Jean-Baptiste Martin, ‘A Stag Hunt at Versailles, c.1700)

The trees were gently heated in a bed of composting tanner’s bark and coaxed to take up water. The earth they arrived in was combed out of the roots and new compost added as they were planted in boxes to ease their annual migration in and out of the greenhouses. These planters had a removable side so the tree could be planted up as it gradually grew in size; the citrus collections were not a throw-away commodity but a continually developing colony. We should not be tempted to think of this collection as made up of lollipop-shaped bushes in pretty containers. Margam was particularly known for the maturity of its citrus trees whose scale can be judged by the practical barn-sized doors at the rear of the Orangery.

‘Size & Excellance’

Walter Davies’ (Gwallter Mechain) report for the Board of Agriculture (1815) refers to Margam’s orangery as the collection of plants and the building as the greenhouse:

The present collection of fruit trees consists of Seville, China, cedrat [a variety of citron], mandarin, pomegranate, curled leaved and nutmeg oranges [kumquat], lemons, citrons, shaddocks [pomelo] and bergamots [used to flavour Earl Grey tea] we measured some of the latter that were 17 inches in circumference. The trees in the green house are all standards planted in square boxes to be removed during summer into the open air in an extensive area surrounded by numerous forest trees and shrubs, tulip trees, acacias, bay trees, arbutus, Portugal laurels, hollies, stone pines &c of the most luxuriant vegetation and a circular pond in the centre for occasional watering. The moveable fruit trees are in number about 110 and many of them are 18 feet high. There are about 40 in the conservatory planted in the natural earth and traced against a trellis framing where the fruits abound and attain their native size and excellence.

Walter Davies describes the extraordinary system of air-rooting (‘circumposition’) used by the gardeners in Margam to propagate valuable trees. Possibly parallels to a stable of pure-bred horses is not that far-fetched. As with horses, dogs, deer and perhaps even your family, it was all about breeding and pedigree.

The Citrus Gene Pool.

The origins of the citrus genus lay in areas stretching between India and China. The first fruits that came to Europe via the Arab world would not be commonly recognised today. The type of orange that made up the majority of the early citrus collections is what we know as the sour or bitter Seville, still required by marmalade makers. The basic techniques of horticultural management were based on the needs of this handsome species. The sweeter oranges, referred to as ‘China’, were naturally more highly regarded but were even more tender than the bitter Seville, requiring more cosseting. The citron was the one of earliest citrus species to be widely grown in Europe when it arrived from its far Eastern home via the Middle East. With its comparatively dry flesh and very thick peel, it can be thought of as a wilder sort of lemon, certainly more so than its hybridised descendants. Citrons had an admired fragrance and, more practically, made good grafting stock for other citrus species. For those reason they held their place in collections over the centuries, despite their very variable appearance. The shaddock we know better as the pomelo, (Citrus grandis). This very large, thick-skinned species was raised in Barbados from seed brought from the Far East by an enterprising Captain Shaddock . No records of the have been found of this captain, but the story reflects the importance of the West Indies in the citrus trade, not least as the pomelo accidentally hybridised to give us the grapefruit (Citrus x paradisi) with which it was at first confused.

The pleasure that could be gained from a citrus collection was not solely the harvest of fruit. In fact oranges had at one time a bad reputation for fruiting in their British palaces, although the Margam trees that were planted in the ground against the heated back wall of the Orangery were famously successful. In the summer, the trees were placed outdoors in a fragrant circle as an instant Mediterranean grove. A central, circular pool in front of an orangery is a feature of the Orangerie at Versailles (finished in its current state in 1686), the progenitor of so many grand designs. In their winter lodging the fragrance drifted into the pavilions at either ends of the orangery where sculptures and models were on display. The latter were acquired on the Grand Tour undertaken by Thomas Mansel Talbot between 1768 and 1772. In an otherwise rather hectoring letter from Nice to his gardener George Bartlett he shares his memorable experience of witnessing the natural growth of oranges, trees that he only had seen protected fretfully every winter back home.

The orange trees grow here with very little care in the corn fields and gardens. Not far from hence is a mountain cover’d with arbutus & Myrtyll & inumberable [sic] quantity of other shrubs that I never saw in England.

[Nice, 20 Nov 1770]

In answer to at least one rendering of the poet Goethe’s knowing question, ‘Do you know the land where the citron bloom?’, TMT did and had succumbed to its enchantment.

Orange blossom. (Botanical Gardens, Singleton Park, Swansea). Given the right conditions citrus can flower and fruit continuously.

The Orangery is now used for functions and events, but there is a recently renovated, late-19th century lean-to greenhouse, or orange wall, (pictured) at Margam Park that contains a modern citrus collection.

After his return to Margam in 1771 to bury his sister, he returned to Italy, there to write to his gardener and brother about a consignment of trees he had bought to enhance the Margam collection, ‘I think there was 6 cedras [citron] & one particular species of orange that bares very small fruit & has a little leaf’, (Milan, 26 Oct 1771). The latter appears to be the small-fruited myrtle-leaved orange that appears in a later inventory. These were being shipped from Bristol to Neath at the same time that Thomas Mansel Talbot was organising the shipping of his sculptures from Italy to either Cork or Dublin to reduce import levies. In a perhaps not untypical mixture of business and pleasure he hoped to transfer them from Ireland to Margam via the ships that carried his coal to and from Taibach, the local port before Port Talbot was developed. Whether the new citrus trees were acquired in this country (home-grown trees were available at this time) or originally sent from Italy is impossible to say, but it is clear that he had seen his purchases with his own eyes.

From 1786 to 1790 the work took place at Margam to replace the existing greenhouses that housed his citrus collection (possibly two, a lower and an upper) with the current ‘citrus palace’ designed in an imposing Classical style. This was structure that protected the oranges from the northern winter whilst providing a handsome gallery for acquisitions from his tour: modern copies of antique sculptures, excavated fragments, models of notable buildings and a bust of himself. It may be termed today an ‘immersive installation’. In creating a walk-through souvenir of his Grand Tour he was not unique. However, there was at Margam an additional element of sensory gratification and recall. Despite the size of the Orangery it not a place to show these precious objets d’art in winter. The gardeners had to continue watering the evergreen plants and work on keeping them in prime condition. For instance, those trees that were taken in too early could burst into unhealthy growth that had to be dealt with. The two end pavilions allowed for a cordon sanitaire for the marbles and models, away from overfilled watering cans and wobbly ladders. Open internal doors allowed the fragrance of the still-flowering trees to diffuse throughout the whole building. The diarist John Evelyn had described the perfumes of orange, citron and jasmine as ‘the peculiar joys of Italy’.

A citrus collection was maintained at Margam until the Second World War when the orangery was requisitioned for military use and was occupied by American forces. The orange trees were left out of doors and failed to survive the winter.

The Citron.

I am particularly interested in the citron. Thick with pith (albedo) it is today one of the sources of the confection that goes by the plain name ‘mixed peel’. The citron was possibly the only citrus that the ancient Greeks and Romans knew. They considered it an exotic medicine as its binominal name, Citrus medica, still records. Presumed by Theophratus to be an anecdote to poison, it could be associated in medieval and early modern times with the archaic anti-poison mixtures theriac and mithridatium. Rich in aromatic oils, citron flesh could be distilled to make a fragrant water, indeed the floor plan for the now gutted Victorian mansion at Margam still maintained the fantasy of an old-fashioned ‘still room’ that was most likely a drinks pantry handily positioned near the billiards room.

Citron (Citrus medica). (Rik Schuiling, Tropical Crops)

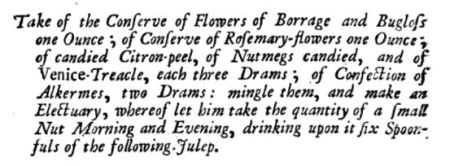

Candied citron peel (succade) came into Europe via the Arab world along with the first citrus trees. Sweet, fruity and resinous it too was considered to preserve the medicinal qualities of the fruit. Francis Bacon listed citron rind as a basis for a cordial, i.e. a medicine that invigorates and stimulates. Here is a medicinal recipe including candied citron peel from Thomas Sydenham.

The Whole Works of that Excellant Practical Physician, Dr. Thomas Sydenham, 8th ed. Corrected from the Original Latin, by John Pechey, M.D. 1722.

I have always had a liking for mixed peel, and consider traditional Welsh tea cakes like teisan lap best when they taste of its vaguely exotic flavour. Shop-bought candied peel is perfectly fine, but homemade peel is softer in texture has a headier flavour. As several have noticed (see Jane Grigson’s Fruit Book) the surrounding cake appears to be infused with it.

I cannot promise you an orangery of fragrance with this recipe but it is an experience of perfumed sweetness and pleasure and, as even Marie Antoinette was claimed to have observed, absolutely anyone can eat cake.

Recipe

Making something delicious from what is often a waste product is kitchen alchemy to me. This recipe is from the BBC Good Food website. The link is here, just in case unforeseen policy changes mean that the recipe disappears or is moved I have pasted it below.

Not an ‘easy peeler’.

Thick-skinned oranges of the navel type seem ideal for this. Oranges that are sometimes found in street markets that might not have the best flavour to the central flesh but have a thick white pith works well for candying. You may wish to assess the discarded peel from a batch of juicing oranges. Citrons are hard to come by, at least in south-west Wales, but if you look around until you find a plump lemon that strikes you as a subject of a 18th century still life (especially one from Spain, such as by Zurbaràn) you are probably on the right track.

Francisco de Zurbarán Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose, 1633

Note: The first boil takes out some of the bitterness of the peel, the second boil can be extended to give a softer end result. I found the period the cooked peel dries – until it is no longer tacky to the touch – can be much longer that the hour the recipe describes; particularly if you have boiled it well. The remaining sugar syrup is too good to waste and can make a delicious ‘citrus peel’ ice cream; almost worth the effort in itself.

‘Ingredients

2 unwaxed oranges and 2 unwaxed lemons

granulated sugar

Method

“Cut the fruit into 8 wedges, then cut out the flesh, leaving about 5mm thickness of peel and pith. Cut each wedge into 3-4 strips.

Put the peel in a pan and cover with cold water. Bring to the boil, then simmer for 5 mins. Drain, return to the pan and re-cover with fresh water. Bring to the boil, then simmer for 30 mins.

Set a sieve over a bowl and drain the peel, reserving the cooking water. Add 100g sugar to each 100ml water you have. Pour into a pan and gently heat, stirring to dissolve the sugar. Add the peel and simmer for 30 mins until the peel is translucent and soft. Leave to cool in the syrup, then remove with a slotted spoon and arrange in 1 layer on a wire rack set over a baking sheet. Put in the oven at the lowest setting for 30 mins to dry.

Sprinkle a layer of sugar over a sheet of baking parchment. Toss the strips of peel in the sugar, a few at a time, then spread out and leave for 1 hr or so to air-dry.

Pack the peel into an airtight storage jar or rigid container lined with baking parchment. Will keep for 6-8 weeks in a cool, dry place.’

An early photograph (c. 1845) with Margam Orangery as its subject, by Calvert Richard Jones (Victoria & Albert Museum)

Left. Might the book collection that was housed in the library pavilion of the Margam Orangery included a copy of the great compilation of citrus species & varieties, Johann Christoph Volkamer’s Nürbergisches Hesperides (1708)? A visual record of the competitive cultivation of citrus fruit among the wealthy merchants of Nuremberg in the early-18th century, the grotesque fruits appear to loom over the landscape.

Right A lemon-shaped cloud from the Port Talbot works’s coke ovens appears to be attempting to imitate Volkamer’s illustrations.

Some Sources

The Penrice letters 1768-1795, Joanna Martin, West Glamorgan County Archives Service, 1993.

Margam Orangery, A masterpiece of eighteenth-century architecture. Patrica Moore, Glamorgan Archives Service, 1976.

Painting Paradise, Vanessa Remington, Royal Collections Trust. 2015.