The Cambrian Welsh or Mountain Sheep

Is of the Ovine race,

His conversation is not deep

But then—observe his face!

Hilaire Belloc’s More Beasts for Worse Children (1897)

I had mixed feelings, to say the least, when Professor Edible returned from The Jolly Butchers with a bag of mutton. ‘The Jolly Butchers’ is not a backstreet pub where nefarious meat transactions take place – we can leave that to the bulk meat trade (see here about the on-going European meat labelling scandal ) – but they are the friendly staff at the dependable Huw Phillips stall in Swansea Market.

Curious about mutton, we thought Huw Phillips could be a good source and in the upshot he was, but first we had to wait. The mutton promotion campaign had done its job in creating a demand and by the end of last year the butcher had access to sufficiently aged creatures to supply this almost obsolete meat to his clamouring customers (mutton is now supplied on alternate weeks from two Gower farms). So why my exasperation on its appearance in the kitchen – as well-expressed by tourist’s face in the illustration? The meat I looked upon so ungraciously was a handful of neck pieces (that is, boney cuts). I had hoped to get my mutton experience off the ground with something simpler, like diced shoulder. For, the one thing I had comprehended about mutton, you have to get it right. Evidence from ‘the literature’ was not encouraging; badly cooked mutton had the reputation to lead inexorably to a challenged digestion, a bad night, a grumpy day, argument and eventual ruin …

There have been many articles in the press designed to entice, and ease the way for, the mutton novice. However, like much food journalism it had the opposite effect, at least on me. Some of the cases made for mutton were less than convincing; if you marinate mutton long enough they taste just like lamb! The techniques gleaned by journalists from ‘top chefs’ seemed dispiritingly elaborate – did the simple cottager real have access to caper paste on a regular basis?

I sat in a gloomy kitchen and thought gloomy thoughts; eventually, I reasoned, an old-fashioned meat needs an old-fashioned recipe. A reprint of Dorothy Hartley’s Food in England (1954) has been resting for some time in our dusty reference section rather

than the food-stained working library. Now was the time to put it thought its paces. Dorothy Hartley (1893-1985) collected social history in a similar way to how the earlier Cecil Sharp collected folk songs. In addition to libraries her sources included the roads and by-ways of this country which gave her book an authentic and eclectic content. A headmaster’s daughter from Yorkshire she gave up her art teaching career to move to her mother’s birthplace at Froncysyllte, near Llangollen to write Food in England (which, like similarly titled books of that time, happily included Welsh, Irish and Scottish material).

Dorothy Hartley calls this recipe a lobscouse, a variable dish of undecided origin it is nevertheless ubiquitous, being the alleged ancestor of the Lancashire hotpot and Welsh cawl, among other regional dishes. Alan Davison (The Penguin Companion to Food) has a good entry on it. There he explains its connection to the sea and ships; similar thick stews of meat, vegetables and ship’s biscuit (here replaced with pearl barley) include the German Labskaus and Danish skipperlabskovs. Particularly associated in the UK with the port of Liverpool it is, if you haven’t guessed it yet, the much mooted origin of the Liverpudlian ‘scouses’ or ‘scousers’. The right sort of consistency for the stew is apparently a key element, mushy enough to spread on bread but firm enough for a (ship’s?) mouse to run over it. If that hasn’t put you off I tell you how I cooked it.

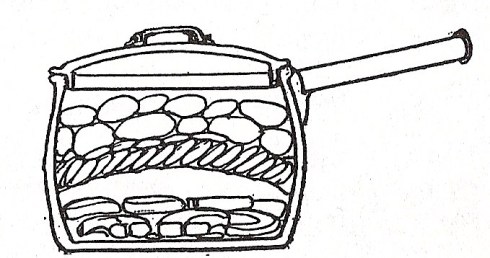

Invoking Dorothy Hartley has given me an opportunity to reproduce some of her very attractive artwork. In fact this little illustration is almost a recipe in picture form.

The neck pieces were browned, after they have been rubbed with a mixture of pepper and thyme. The meat pieces were placed together in a single layer on the bottom of the pot. Above this the sliced root vegetables were added; I had carrots, turnips and

swedes. Leeks, as DH states, give a more delicate flavour but onions are allowed too. I included some garlic cloves that, like much else, were destined to disappear into the mixture by the end of the cooking time. A ‘sprinkling of barley’ in lieu of ship’s biscuits helped the finished dish thicken up. After seasoning with ‘mountain herbs’ – which I interpreted this time round as thyme and rosemary – a layer of sliced potatoes covered everything. After adding water up to the potato layer, makers of Lancashire hotpot would put down their tools, but this recipe has a clever idea that unfortunately I couldn’t test this time. Whole potatoes are placed on the top to cook above the water level but under the lid. When these ‘canary birds’ are cooked it is said that ‘the meat will be just leaving the bone’. I could have kicked myself as I’d run out of potatoes by then; I will update on this technique when I can.

Cooking in a slow oven I perhaps left it a little too long (2 to 2 ½ hours would have been fine) but leaving the pot completely undisturbed I wanted to be sure of a sweetly

gentle cook. The result simple but delicious, it had its own subtle rich flavour which has won us over. DH quotes George Borrow’s colourful Wild Wales (1882):

Certainly I shall never forget the first Welsh leg of mutton which I tasted, rich but delicate, replete with juices derived from the aromatic herbs of the noble Berwyn, cooked to a turn.

To finish this post in praise of mutton here is a happier depiction of a sheep than Hilaire Belloc’s blank face mountain creature. DH clear was of those aficionados that believed, unlike Belloc, in intelligence and character of the ‘Ovine race’.